Raphael’s Women and the Universal madonna

Madonna della Seggiolla, 1513-1514, Raphael

But he nevertheless realized that he could not reach the perfection of Michelangelo in these matters, and, as a man of the soundest judgement, he considered the fact that painting does not consist entirely in creating naked men, since it has a wide range; that among painters who have reached perfection can be numbered those who know how to express the imaginative composition of their scenes with skill and facility and their fantasies with sound judgement, and who in composing their scenes know how to avoid confusing them with too many details or impoverishing them with too few, and how to organize them in a creative and orderly way; and that this kind of painter can be called a talented and judicious artist. To this conclusion, as he continued to think about the problem, Raphael added the idea of enriching his works with the variety and inventiveness of his perspectives, buildings, and landscapes; a graceful way of dressing his figures, so that sometimes they disappear in the shadows and sometimes stand out in the light; a way of creating lively and beautiful heads for women, children, young men and old alike, and to give these, as necessary, a sense of movement and vigour. He also considered the importance of a painter's skill in representing the flight of horses in battle, and the ferocity of soldiers; the knowledge of how to depict all sorts of animals; and, above all else, the method of painting portraits which resemble men who seem so alive that one may recognize the person for whom they have been painted as well as countless other details, such as the style of garments, footwear, helmets, armour, women's head-dresses, hair, beards, vases, trees, grottoes, rocks, fires, overcast or clear skies, clouds, rains, lightning bolts, calm weather, night, moonlight, brilliant sunshine, and numerous other things which are still essential elements in the art of painting. - The Lives of the Artists, Giorgio Vasari, 1550

To begin near the end: Raphael’s Madonna della Seggiolla is known to be one of the legendary painter Raphael de Urbino’s later depictions of the Madonna, but who commissioned it and when and where it was executed are still mysteries. Georgia Vasari does not even mention it in his gargantuan Lives of the Artists, a contemporary yet occasionally divisive firsthand biography of the key figures of the Italian Renaissance. The Madonna della Seggiolla has remained one of the painters’ most celebrated Madonna paintings, praised for its humanistic elements.

In it, the Madonna appears to us lightly flushed, cradling the infant Christ, whose left arm reaches into his mother’s green dress for warmth. Mary’s arms wrap around him and her legs, which are covered in a blue material, lift to support his back. As with many depictions of the Madonna with child, an infant St. John peers over from behind Christ, looking up at Mary. Forcellino, in Raphael: A Passionate Life, says that the triangular composition in the Madonna della Seggiolla “creates a strong sense of physical and above all, psychological contact” which recalls Leonardo’s Madonnas, but this essay aims to analyse elements of Raphael’s approach to painting women, men, and people that maintain as quintessentially, well, Raphael. It’s this ‘psychological contact’ that Raphael saw in Leonardo’s work and imbued- and deepened- in his own work.

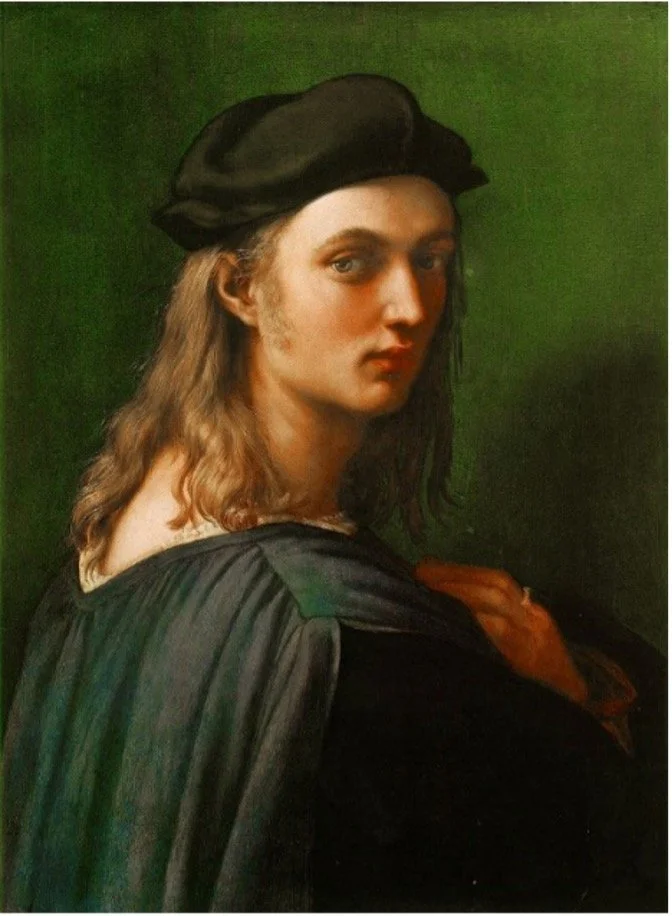

Self- Portrait With Friend, 1518-1520, Raphael de Urbino

Raphael was born in the city of Urbino in 1483, the son of a court painter, and died 37 years later, leaving, despite his relative young age, a large body of work. Rona Goffen says of the forever-young painter in her comprehensive Renaissance Rivals: “Since the 16th century viewers have recognised that Raphael’s art was shaped and reshaped by what he saw as he moved from Urbino, to Perugia, to Florence, and finally to Rome.” Originally apprenticed to Perugino, he quickly surpassed the old master and turned his attention towards Leonardo, and then Michelangelo. She cites Raphael’s contemporary Paolo Giovio, the physician and historian, who argued that Raphael had ‘attained the third place in painting… by virtue of his marvellous gentleness and alacrity of a talent quick to assimilate’” and that “the history of Italian Renaissance art would have been very different had Raphael stayed home. His work represents the most conspicuous demonstration of the effects of imitation…”. His work is charged with a certain kind of charisma and romanticism that other Renaissance artists- even technically more masterful ones- lack. When I visited the Uffizi in Florence, it was of course Botticelli, Artemisia Gentileschi and Caravaggio that drew the most gasps from the visitors around men, but of all the famous masters, it was Raphael who quietly drew the most curiosity. “I think Raphael was my favourite”, I heard one woman muse as she exited with her partner. His characters strike you as more modern, more mischievous, and less divorced from reality: they are lively. Unlike Leonardo and Michelangelo who seemed to come out of the ether with formed artistic voices, “Raphael’s earliest paintings allow no intuition of his future”. This is the key to his power as an artist- his study of people in their diversities and quirks, and his eye for cultural detail are as important as his skills with a paintbrush.

Back to the della Seggiolla: Forcellino notes “the fashionable turban alla turchesca” that she wears. It is important for Raphael’s women to be “fashionable” as it is what makes his female protagonists so progressive; he never sacrifices femininity in his attitude. His women were multi-dimensional; they could be devoutly religious and maternal whilst also showing off culture, gilded furniture and imported fabrics. And yet it is unmistakably mundane, creating “that miraculous feeling of unexpected poetry”, as if the viewer has stepped in on the unassuming mother, rather than posing for them. “Raphael’s painting constantly uses reality…a process that has been repeatedly attributed to the influence of Neoplatonic thought”. Significantly, Madonna looks at us, implying that her love isn’t limited to her son- maternal love is universal.

It is hard to find depictions of the Madonna gazing at the spectator. Antonio Forcellino argues in his emotionally charged and vivid biography of the painter Raphael: A Passionate Life that in contemporary Italy “it was more usual for her [the Madonna] to be enveloped in the psychological dialogue between mother and son… impenetrable.”, but here, she asks us to “share the melancholy and tenderness that make her hug the restless child tightly”. The scarf adds a “note of mystery” and uniqueness to the painting; it’s clear that Raphael wanted this Madonna to stand out from the plethora of others. “He refused to repeat traditional models”, Forcellino also adds. the scarf; “appears to have been a masculine accessory” (P.202). “What makes this one so original here is that Raphael uses it to express the spontaneity of the scene”, the scarf being used to “cover her neck and chest, as if she had grabbed the first thing she found in order to protect herself from a sudden chill”. The scarf curves around her head and neck, isolating and pronouncing her face, and her femininity is enforced by the Titian-esque reds of her cheeks and sleeves and the . Forcellino states: “With this, Raphael had moved as far away as he could from the rigid devotion of earlier Madonnas. This glorification of femininity also becomes a glorification of natural maternity and, as such, was rightly recognised and appreciated in centuries to come by women all over the world”.

Madonna of the Magnificat, 1481, Sandro Botticelli

Take any none-Raphael depiction of Madonna and Child: in Sandro Botticelli’s depiction, his Madonna of the Magnificat, she is writing- some would argue an act of agency. Rather than a feminist statement, however, the golden, almost glowing skin of this Madonna, the angels flanking each side of her, crowning her (one holding the book steady for her) whilst the infant Jesus guides her hand, alludes to a sense of guidance, or even entrapment. There is no freedom here, no agency: she is flanked on all sides. She doesn’t look at the viewer, but if she did, her eyes might scream for help. And yes, she is writing, an act of agency, but as Schibanoff (1994, p.1) points out, it “attempts to persuade the viewer she is an impossible figure” with the general aura of heavenliness. Contemporary studies of feminism in might suggest that “othering” women- in Botticelli’s case, heroizing them- is regressive: Griselda Pollock, for example, states: “The sign of an always sexually differentiated and differentiating convergence of masculine and feminine interest is the 'mother', a sign in psychic fantasy… whose 'murder', or perhaps repression, has been consistently identified as a structural necessity for, and a founding myth of, patriarchal societies… Women as representatives of the Mother- are not Heroes”.Women can be beautiful icons of femininity, or trade that femininity for ‘masculine’ aspects of power- mutually exclusive paths. This analysis obviously cleanly applies to much of Biblical history, which has heroized as often as demonised women from Mary Magdalene to Mother Theresa. Vasari is stunned in the Lives to find women capable of artistry; describing Properzia Rossi as “extraordinary”.

For arguments sake, then, let us say that the icon of the Mother is inherently sexist in Western history. Let us also clarify that in a Catholic era which indeed celebrated religious figures that were women; to go against the grain would not be to idolise them but to depict them realistically. The point of this essay isn’t to apply 21st century standards of feminism to Renaissance work but simply to point out how Raphael’s Madonnas and indeed his depiction of women stands out from his contemporaries and yes, is inflected with a surprisingly progressive dimension of feminism at times.

A Brief Sojourn to Florence

Portrait of Agnolo Doni and Portrait of Maddalena Donni, 1506, Raphael

Although Raphael spent only four years in Florence, and was reputedly never an actual resident there, this is a relatively lengthy time for the short-life of the tireless worker Raphael de Urbino. Here Raphael, now-already, at this stage of his career, a sought-after prince of Christian artistry, evolved from his thematically ambiguous work in Urbino and Perugia. In Florence it’s where this “great versatility” Vasari talks that begins to bloom: especially in his unique approach to tradition and gender. The prior portraits of Agnolo Doni and Maddelena Doni, (1506) begin to show it subtly. Technically proficient portraits, Raphael blurs the gender-binary between the married couple who have commissioned him; perhaps implying that in marriage they have transcended societal boundaries and have entered a world of their own. Agnolo’s mouth “has an almost feminine fullness” according to Forcellino, but more importantly is Maddalena, who’s undershirt is coming out of her dress, as if her real self is bursting at the seams of her containment. Her hair, as rigid as a snake- has some remarkable tendrils spiralling to her left and dangling, escaped hairs to her right “as if a mischievous breeze was trying to breathe a quiver of life into such immobility”.

I would argue this “mischievous breeze” that places her “in an everyday world”, comes from Maddalena herself. Like the Mona Lisa, a work Raphael certainly studied, Maddalena is in a three-quarter pose, but Raphael eschewed Leonardo’s sfumato, the technique where colours are blended to imply a blurring between subjects. Raphael’s portraits are carefully spatially organised to emphasise a total serenity in this Edenic new world of married life the couple has entered, and as such Maddalena is now powerful enough to be pronounced in the composition; the tree in the background is placed almost at her eye level; she exudes a whirled energy that spikes her hairs into disarray- if you look closely enough; and the tree looks still, as if to say contrast with Maddalena’s restrained-but-unmistakeable windsweptness, to say that a woman can never be as immobile or as unchanging or as timeless as a natural elements. Perhaps Raphael adorns so many of his women with fashionable garbs to bring them out of the infinity of nature and into the waking changing world of reality.

As David Alan Brown states: “This work is exactly contemporary with Leonardo's Mona Lisa, but there is nothing enigmatic about Maddalena's stolid self-presentation to the world. If Leonardo drew the female portrait in the direction of fantasy and poetry, the young Raphael pulled it firmly back in that of realism and prose. The central role that naturalism played in Raphael's aesthetic—his interest in the specifics of Maddalena's somatic adornment and lineaments—underline his different understanding of the role of the portrait”. Raphael’s women are a source of intrigue only in their naturalism and styles- the polar opposite to Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, the source of the greatest mystery and emotional distance in history, a puzzle-box.

The Miraculous Draught of Fishes 1515-1516, Raphael de Urbino

“Realising that he could not reach the perfection of Michelangelo”, Raphael began “…enriching his works with the variety and inventiveness of his perspectives, buildings, and landscapes”, said Vasari, echoed by Goffen, who writes that Raphael developed an “interest in landscape, always a significant element for the composition and the psychology of his works, but always minimalistic to Michelangelo…”. It’s an approach to nature he continued to use, as in The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, where Forcellino argues that “the calm surface of the lake… stretches into infinity” and is echoed in portraits like Young Woman with a Unicorn (1505-1506), or Portrait of Elizabetta Gonzaga (1504-1505). Raphael placed women in islands of “immobility”, with simple, unchanging backdrops with peaceful, controlled brushstrokes but contrasts them with women whose complicated, fourth-wall breaking stares suggest timelessness. Raphael placed his women in landscapes, sure, but the landscapes are secondary to the visual power his women possess.

Young Woman with Unicorn, 1505-1506 Portrait of Elisabetta Gonzaga, undated, Raphael de Urbino

Taddei Tondo Raphael after Michelangelo, 1505 Small Cowper Madonna, 1504-1505, Raphael

Raphael’s explorations in Florence continued and resulted in some of his most transgressive works. He began to literally deconstruct the Madonna with Child scene in Florence, even taking out John the Baptist in many versions, like the Small Cowper Madonna and the tondo sketch after Michelangelo. Goffen, again, whose book I can’t recommend enough, states:“he focused on the Virgin and Child…in copying these two figures, Raphael eliminated much of Mary’s veil so as to isolate her lovely profile. She is one of Michelangelo’s more feminine Virgins, and Raphael feminized and classicized her further. Especially in the second drawing, he removed much of her drapery and indeed much of her body (except for the neck, shoulders, and a hint of her left arm) in order to concentrate on the Child… in Raphael’s drawings, Christ attempts to escape from something not shown, leaving to the beholder’s imagination the sight that alarms him”… Implying that for even the best mothers, parenthood necessitates a difficult tension more akin to Simone De Beavouir’s memoirs of pregnancy; only noble in its pursuit of humanism despite its hardships- and not blessed by some higher power that makes the process easy. The same can be said in his Bridgewater Madonna, where Christ tugs on his mothers scarf, curved almost in a horizontal serpentina figurata, a display of twisting tension.

In this last emendation of Michelangelo’s piece, Raphael “achieved a… psychological subtlety.. characteristically… his depiction of the relationship between Mother and Child is more intimate. Bound by their gazes, they suggest a dialogue: Christ questions his Mother and she answers with affirmations of his destiny.” But the future she tells of doesn’t sound like one of sunshine and peace, but of responsibility and tension, one which will end in tragedy.

Rome’s Impressions of Gender

Bindo Altoviti, 1515 and Isabel of Naples 1518 Raphael

It was in Rome that Raphael found the perfect source of societal inspiration and an adoring audience: benefiting in multiple ways from the “new sentiment of eros and female sensuality”, in the “free and liberal society of Rome at the peak of his virility”. Here he painted a world of vibrant, complicated, many-hued Italians who were sexual and devotional; not heroic or angelic.

In Bindo Altoviti, Raphael “eroticizes its male subject in ways more usually associated with Venetian images of anonymous beautiful women”, just look at his half-turn stance as he peers out of shadows, his lustrous hair ‘caressing’ his exposed neck, with a hand to his vulnerable heart. This is quite the distinction compared to the contained maturity of Isabel of Naples. With Raphael’s portraits up till this point, he had used landscapes to merely gesture at women’s interiority, but with the Isabel, he paints her like he would a man; knees apart, her arms are splayed out, she is, again, candid, in Forcellino’s moment of “unexpected poetry”. Here, he makes his boldest feminist statement yet. Although Guilio Romano completed the painting under contract from Raphael’s workshop, Raphael sketched the scene and, according to Vasari, completed her face. As Goffen describes it: “the Isabel monumentalises the subject… The garment, jewels and other trappings of rank are painted with far more attention to detail- literally individualised- than the face, so psychologically remote as to seem frozen, so smoothly painted as to seem porcelain”. If his other portraits showed a woman with, say, a window into the wilderness of her psychology by way of a landscape; Isabel takes the inverse approach, and the sliver of blue sky between two columns pales in comparison to the monument that is Isabel herself, an unstoppable force, or an immovable object. Although Raphael’s contributions to this piece seem to be limited to its conception, Forcellino says "it is no coincidence that Raphael conceived the type for a female subject… Isabel faces her beholder, but her trappings, her pose, her domination of the composition, and above all, her sang-froid, protect her from a beholder’s misjudging her status, that is, both her moral and her social condition”. Raphael had toed the line between empowering his women subjects and questioning the reductive qualities of the patriarchy and created a fashionable, Trojan-horse female portrait that influenced art for centuries to come. Even Joanna Woods-Marsden, who argues Renaissance women “were no more empowered in art than in life” and that their portraits usually embody the “Renaissance social construct of the patrician female ideal”, concedes that the Isabel of Naples is the “exception… the only female sitter with both the power and the knowledge to effect the artistic outcome—ironically, seldom to her satisfaction”.

The Monumental Female Image

Peasant Woman Stooping, Seen from Behind, 1885

Pollock equates depictions of size in painted women as relating to arguments of beauty and disgust. Van Gogh’s Peasant Woman Stooping, Seen from Behind, 1885, for instance, as a “massive, almost giantesque” figure that “suffers moments of significant disproportion… An overlong arm emerges, jointless… ending abruptly in a huge fist - almost larger than the figure's head. The scale suggests an archaic, maternal body, vast and impossible”. This is obviously a world away from the high-class clients of patronage that Raphael was commissioned to paint, but Pollock’s description- in words- could be describing the Isabel. By placing a bourgeoisie woman- the kind he’d associate and tryst with at the courts with his progressive peers like Baldassare Castiglione- adorned and facing the viewer but painting her in a relatively ungainly and cumbersome snapshot, Raphael usurped conventions and surprised the art world with the help of Romano. “Raphael”, says Forcellino, “was close enough to the court and to that elite to anticipate the appearance of new women on the social scene, women who moved away from the devout, maternal role assigned to them for centuries by the Catholic iconography”. Paola Tinagli reminds us that the Isabel was made to celebrate her social-class and her beauty, and as such Raphael takes a different approach to her than he did to his Madonna’s, creating a sense of “distance and awe”- there is no maternal, inviting gaze, but a powerful, perhaps abrasive one, and this is just one example of how many kinds of women were represented in Raphael’s paintings.

Goffen says of the Isabel: “Just as Raphael had interpreted Bindo Altoviti with the sensuality usually associated with women”, he approached the Isabel “as though she were a man though without compromising her femininity. Raphael’s ability to bend or abandon traditional pre-suppositions about gender and demeanour helps explain one of his most admired portraits, treating a male subject with the kind of emotionalism and psychological vulnerability that might have been more expected of a woman.” Tinagli also posited that Raphael was the kind of humanist who could depict multi-dimensional women: “Raphael’s portraits are different from Leonardo’s in that they are studies of social beings”, and she believes Raphael had an “interest for the peculiarities of the sitters features. Raphael succeeds in bringing together a sense of the individual and her place in society” As opposed to the other masters then, Raphael’s focus on “social beings”, brings us to study the daily minutiae in his work, like clothing and landscapes: Brown argues: “Offering a more passive construction of gender, Raphael domesticated the older artist's inventions”.

Forcellino announces that Raphael “held the keys to the world of beauty”. “Far from maintaining the craftsmen-like tradition of… stories in keeping with the biblical tradition, Raphael was now creating cult objects that held the capacity to liberate spiritual feelings in humans, linking them to a higher world”. Raphael painted a universal idea of beauty, stripping humans to their essences. There is little need to fear beauty standards in his work because it is a level playing field where no matter what the rich wear they slouch just like the poor, where gender is flattened, and the only real beauty can be found in connection: between spirit and style, between the eyes of the subject and the eyes of the viewer, between the image of a Mother and what she elicits in us when one of the many billions of her children look up at her.

Conclusions: The sistine Madonna and the La Fornarina

The more complicated Raphael’s women got the more striking his allegories became. In The Sistine Madonna (1513-1514) and La Fornarina (1518 - 1519), he uses the Italian theme of revelatio through visual metaphors- the parting green curtains in the former, and the see-through veil in the latter- the woman finally revealed in each.

The Sistine Madonna (1513-1514), Raphael de Urbino, and La Fornarina (1512) Raphael de Urbino

The Madonna stands on the clouds surrounded by cherubs and saints, yet still Raphael achieves a degree of realism. Forcellino states that in contrasting the “luminous background” with the Madonna’s darker robe, a “stateliness” appears, the worn, broad-shouldered visage of real life motherhood-as in Bridgewater and Seggiolla, there belies a physical strength. She lands on the cloud, clothes ruffled, and despite “the mystical wind, her left leg is bent, changing the light on the heavy purplish cloth”, emphasising the weight that carrying a child of prophecy necessitates-again, a “monumentality”. “Through Raphael’s brushstrokes, female beauty passes with unfaltering assurance from the erotic register to the devotional”. The curtains of Christendom have parted to reveal a real woman.

In La Fornarina, his most intimate portrait (whether the sitter really was his lover or not) Raphael binds “the two most basic prototypes of the female- woman as lover and the woman as nourisher”, argues Goffen with one hand covering-and in so doing, gesturing at a nude breast, and the other her genitals. She is both things at once. A see-through veil covers her abdomen. Fornarina may count as "the first time that this three-quarter view is used in Raphael's work for someone not known to belong to the nobility…. La Fornarina is also dignified by the direction of her gaze… avoiding eye contact with the beholder. This fact, together with the three-quarter figure and, above all, Raphael's name on her arm, combine to shield her, despite her nudity-that is, to protect her… from his imagining that he might, by gazing, possess her”: but it isn’t despite her nudity, as Goffen suggests, that she projects an aura of power and safety, but because of it. The slipping veil has been half forgotten, her strength lies in her comfort; the nudity isn’t the point but a footnote to the work, and perhaps it is the viewer who is humbled- she doesn’t even grant the viewer a magnanimous glance. La Fornarina is maybe the final painting Raphael completed- of his lover, no less, and it is charged with emotional and psychological energy. If you’ve read this article looking for the bottom-line: was Raphael a feminist? Then La Fornarina is the painting that will give you as close to an answer as you can get. And yes, you could read that infamous arm bracelet with Raphael’s name on it as a suggestion that she is his property, that Raphael maintains ownership of some kind- but I choose to see it as one of his wittiest details: for once, the man as accessory to woman.